Looking at so much art, seduced by the natural landscape, the Kerala Mundu, Arabian Sea and delicious beyond delicious Malyali cuisine, my senses were satiated - well, close to being saturated. But, there was more to see - a hell of a lot more. How does anyone see it all, I wondered as I made my way back to Aspinwall House for the nth time.

Looking at so much art, seduced by the natural landscape, the Kerala Mundu, Arabian Sea and delicious beyond delicious Malyali cuisine, my senses were satiated - well, close to being saturated. But, there was more to see - a hell of a lot more. How does anyone see it all, I wondered as I made my way back to Aspinwall House for the nth time.

Of the many nationalities, from Egyptian to Chinese, Arabs, Portuguese and Dutch, who came to Kerala in search of spices to trade, an Englishman by the name of John H. Aspinwall, stayed and made Cochin his home. Originally used for the business of Aspinwall & Company Ltd. established in 1867, this historic building today, is home to many significant art works in the Kochi-Muziris Biennale.

|

| Aspinwall House |

The title given for the 2017 Biennale, by curator Sudarshan Shetty, ‘Forming in the Pupil of an Eye', referring to the eye which is concurrently physical and metaphysical, evolved with the art experience, to be an apt one. For the last three days, each artwork seen, led by the sensuous-loving physical eye, I had absorbed sounds, images and words, with the ‘eye’ simultaneously becoming an invisible mirror to reflect and let the particles of the seen and perceived vision sink deep into the abyss of being; finding oneself - in empathy, in curiosity, unresponsiveness and even playful competitiveness.

|

| Mundus and only mundus, lined up, pile upon pile |

The evening before, I'd bought myself a white Kerala-style man’s ‘mundu’ (loosely translated as lungi) with a simple black border, promising to wear it to the next day’s Biennale viewing. And I did. The salesmen at the shop on Churchlanding Road in Ernakulam had been amused at my quest to learn how to wear it, and each of the seven or eight men in the shop took turns in showing me how to wear it. Each thinking that they would get me to understand what the other had failed to communicate. I was keen to wear it pulled up, from the ankles up to the knees, which was a tad complicated and my efforts gauche and awkward to say the least. The experience had been hilarious for all, me included, even if a little embarrassing. Anjalee and Maggie tried to distance themselves from my keenness to learn how to pull it up, like we had seen men on the street do quite effortlessly. Anjalee had gone so far as to quietly inform the salesmen that I was ‘mad’. That afternoon, the day after the mundu madness at Kasava Kadu, when the three of us met outside the ‘Pyramid of Exiled Poets’, at Aspinwall House, I in my pristine white mundu teamed with a sleeveless black T-Shirt, willingly posed for the ‘must-have’ photo and then we proceeded to look for Raul Zurita's much acclaimed installation - The Sea of Pain', which I'd been dying to see but hadn't yet got there.

I'd seen images on Facebook. I'd read reviews and my expectations were therefore loaded. Drawing on the Syrian refugee crisis, this installation by Zurita is dedicated to Galip Kurdi, the brother of 3yr old Aylan whose body had been washed ashore a Turkish beach in September 2015. The much-photographed image of Aylan becoming synonymous with the tragedy of the refugees who weren't granted asylum. Gurdip, his brother and their mother drowned when their dinghy capsized in its attempt to reach the Greek island of Kos, via Turkey. When the sea got rough, the Turkish smuggler, paid to bring them ashore, abandoned the boat, which capsized. Born and living in Chile, using his art as a vehicle to convey a political message, Zurita makes this crisis a moment of awakening for all. His audience, walking through the installation, bare feet, mid-calf steeped in dark waters, is compelled to listen within and to question what they would do in a moment of such a crisis.

As you wade through a long, dimly lit gallery filled with water that looks black, taking one solemn step at a time, for walking through water cannot be a hasty stride; it comes naturally to look around, to turn here and there. And the helplessness of being abandoned tugged at something in me, heightened by piercing questions, that called out silently but accusingly, from high walls that framed the long and narrow room: Don't you listen? Don't you look? Don't you hear me? Don't you see me? Don't you feel me? Are you never coming back - never? Never?

One step at a time, I walked up to the end of the long rectangular space, to be reminded that a human tragedy is never just someone else's it is also our own, especially when Zurita states: "I am not his father but Galip Kurdi is my son"

Walking back to where our sandals were left, Maggie and I were reflective but in our out-ward path a young girl danced in the water, lifting her dress and pirouetting daintily; her playful form silhouetted against the daylight. There were now many more people entering the installation space, but an experience that touches at the level of soul cannot be thus distracted from its message.

|

| Orijit Sen, 'Go Play Ces' |

As we left the installation, pausing long enough to dry our legs and feet, the next gallery that beckoned my companions was Orijit Sen's 'Go Play Ces'. I protested that it was too much of a contrast after such a solemn, soul-stirring experience. But, followed them nonetheless and was completely taken by the mixed-media installation games that we were invited to play. Visiting the vibrant Friday, Mapusa market in North Goa, is an experience that I've enjoyed first hand but, the details that Sen has captured come from deeper observations than a cursory holiday visit. It was like a virtual journey through liquor shops, the fish and flower sellers and much, much more. And to ensure that some essence of this experience remains, Sen tempts you to answer five questions to win a printed card of his drawings. So, totally engaged in this playful experience, I expected to forget Zurita's poignant plea, but despite exulting at winning two cards, the impressions of being in the ‘Sea of Pain’ remained.

|

| Orijit Sen, 'Go Play Ces' - The Mapusa Market Game |

Savouring deliciously sweet, fleshy, golden jackfruit for breakfast the next morning. I found the questions returning: "Don't you listen? Don't you look? Don't you hear me? Don't you see me? Don't you feel me? Are you never coming back - never? Never?" Abandonment is something we have all experienced at some juncture of our lives. Abandoned by family, friends or lovers in moments when we've possibly felt a need for human succour the most; in a gesture of defensiveness and self-protection, we may have internalised this angst. Therefore, reliving it through art can be cathartic and healing. Even though Zurita had a specific basis for his questions, they are common to the human condition, each with our own personal experiences to remember as we walk through this universal sea of pain.

|

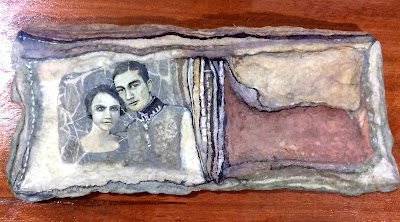

| Desmond Lazaro, Family Portraits, Aspinwall House |

When sorrow is celebrated - and expressing it through art and poetry is about celebration rather than suppression, is where I am reassured that the exalted premium that contemporary society has accorded on happiness, hasn't eroded our capacity to experience its lamenting brother.

|

| ‘Dance of Death’ by Yardena Kurulkar at Aspinwall House writes her date of birth with light bulbs that keep going off, to have all the lights go out at the end of the Biennale |

Each day in Kochi has been an enriching and enlightening one and I want to gush with enthusiasm like a teenager, but restrain myself. Walking through the extensive galleries at Aspinwall, I walked into the ‘Dance of Death’ by Yardena Kurulkar, passed the ‘Family portraits’ by Desmond Lazaro and entered a large hall which had a painted mural in progress.

|

| Desmond Lazaro, Family Portraits, Aspinwall House |

Sitting on raised platforms, two artists, assistants of the painter P.K. Sadanandan, were engaged in completing a mural which depicts a story called 'Paraya Petta Panthiru'. A young gallery guide told us, this is the story of inter-caste marriage and how each child, of the twelve progeny born of this marriage, was abandoned by their father at birth - trusting in the force that created its life to care for it.

This translated into each child being brought up and/or adopted by families of varied castes - from Brahmins to carpenters and wandering minstrels. It's a powerful legend to educate people on the universality of being - free from caste and religious dictates. The father of the abandoned children was Vararuci, a Brahamana scholar in the court of Vikramaaduthyan in 57BCE. Featuring narratives from mythology, masterfully painted in the Kerala mural style augmented with inspiration from the cave paintings of Ajanta and Ellora, although Sadanandan's art, is known well known for his presentation of teachings and practices from across India, it was my first encounter with this painter’s oeuvre.

|

| Anjalee viewing the large scale mural by P.K. Sadanandan |

The intermingling of abstract experiences with vibrant traditional forms in art along with sensory experiences of tastes and smell that have been a simultaneous 'degustation' of the Biennale experience, echoed the philosophical thought in Bose Krishnamachari's essay, in the Biennale Guide. "The river is everywhere" says Bose, quoting Hesse from 'Siddhartha', in a 'A River called Biennale’ as he expounded the likeness of a river to that of the human experience. "We are born of a river's origins and like a river flow toward an end. A river is the root of our existence. All great civilisations were born on the banks of a river". The river is where all things merge. Situated in Kochi, on the banks of backwaters that lead to and come inland from the Arabian Sea, especially at Aspinwall House which is a sea-facing property, it was easy to make this connection of a river's origin flowing into the sea and on its journey carrying the silt of experience, merging into the oceanic current, into the being of non-being - that vast ocean of one-ness.

|

| On the ferry to Ernakulam |

As we'd walked around asking for directions to Zurita's 'Sea of Pain', we'd observed someone blindfolded and being guided in a most aesthetic way. I had been quite taken with what I had seen of this audience-interactive performance. The participant could not see, but I'd watched Jijo guide her to stop or move forward, relinquishing his touch through enchanting, dance-like gestures. Steered by sound (headphones) and touch alone, where goggles shut out the visual, I had watched her being led in and out of spaces at Aspinwall House. Intrigued and attracted by the lyrical gestures of Jijo, her guide, I signed up for the experience and hurried back from lunch at a nearby water-front restaurant, with a quick look at Praneet Soi and an interesting marble sculpture by Jonathan Owen at Pepper House, to participate in this performance.

I hadn't given much thought to what I had set myself up for, but as I waited for the performance to start, I reminded myself how much I rely on the visual to experience life. I'm exceedingly sensitive to sound, but it's the visual that's been my metier. Would that bother me? Soon enough, a hand reached out from behind me and put large white goggles covering my eyes, obscuring everything but a sensation of light. I was now completely at the mercy of my touch-guide and the recorded soundtrack played through the wireless headphones. In anticipation of being taken through 'The Sea of Pain' as part of being masked and walked through familiar spaces, I requested Jijo to turn up my mundu. Thankfully Maggie and Anjalee weren't there to tell me how ridiculous I may have looked and I surrendered to the ‘Symphony of a Missing Room', choreographed by Christer Lundahl and Martina Seitl, enacted by Jijo and myself.

Blindfolded, I was led by suggestive hand gestures, aided by the recorded soundtrack, which alerted me to take slow measured steps or to stop. Pause a bit, then move forward, take a step up or down or touch a wall - telling me I had reached a dead end. The soft, predominantly female voice, played through the wireless headphones, occasionally urged me to see the light within, to imagine the art works I had seen before this, but each time I tried doing so, I could only visualize tall, bending trunks of lofty coconut palm trees, their pinnate leaves moving with and creating a gentle breeze. From the onset of the performance, as soon as the headphones were put on, I also had this inexplicable urge to sleep. I wasn't sure if this was brought on because I was tired or because I found the spoken tract a little naive and didn't connect with embracing change through the Biennale, which I now viewed without sight. There was a shift but it was making me sleepy. I'm aware how fear of facing things does create this illusion, but there had there been no real fear. Not about the performance in any case. I walked with caution but I also knew that I'd be led safely. Maybe it was a deeper fear surfacing, or maybe shutting out the visual created a familiar, sleep-inducing space. Each day had been packed with stimulating experiences, so it could just be that – the surfacing of a latent desire to sleep!

When I was asked how the experience was, the only word I could summon was 'weird'. I hadn't had any kind of spiritual epiphany of experiencing myself at a deeper level of knowing, nor I had I recollected the art works seen in days or even hours just passed. The sensation of wanting to sleep overwhelmed, and the coconut palms all around me, dominated my subconscious. I fought the urge to sleep - I had to, I mean, how could I sleep standing up? As I walked, unknowing where I was, I did experience various degrees of darkness and light, which led me to think I was going inside or coming out into the open which brought about the shift regarding the levels of light. At the end of the half-hour session when the goggles were removed I was standing calf-deep in Raul Zurita's 'Sea of Pain'.

|

| Returning to that inescapable Sea of Pain |

Overwhelmed by the urge to slumber, I headed out of Aspinwall in search of some South Indian filter coffee to find none. I returned to my room in Thoppumpuddy to get my camera and rushed back to Fort Kochi for a Kathakali performance and make-up session. While the experience was photographically enriching - watching them do the make-up was novel, the whole performance was designed for touristy kind of viewing and I was possibly the lone Indian among fifty foreigners.

|

| doing his own make-up |

The man who played the female lead should have retired a long time ago, but hogged the limelight while the younger man who was more interesting in attire and fluidity of movements as well as elegant facial gestures, so vital in Kathakali, was relegated to the background.

When I bought my ticket and a young man guiding me to my seat, softly asked why I was wearing a man’s dress; was it because it was ‘Women’s Day’? I had forgotten I was wearing the mundu, I had forgotten it was the 8th of March and reminded of both in this way, I forgot to tell the young lad that, in the normal scheme of things, I wore a ‘man’s dress’ more often than what is narrowly designated a ‘woman’s dress’.

The interplay of life with art heightened by such unexpected occurrences, my third day at the Kochi Biennale ended with a delectable bite of figs and roasted almonds coated with a delicious dark, dark chocolate. I headed back to my homestay in Thoppumpudy in an auto, reaching just in time before it started pouring down with rain. Although I was relieved to not have been caught in the downpour, it did flash through my mind that Kerala has two monsoons - the south-west monsoon in June and the north-east in October, bring plentiful rain which means that unlike other parts of the country it is never parched. “Falling Down, pooling up, /Out of the sky, into my cup. /What is this wet that comes from above, /That some call disaster, and others find love”, wrote the poet Mitchell. D. Wilson, echoing the paradox where the falling wetness may irk but water and especially rain, is also an integral part of the Kerala landscape. In addition to the extensive shoreline of the Arabian sea on its west, Kerala also has a network of rivers and lagoons with tranquil stretches of backwaters, all of which add to its lush greenness and abundance of natural birds and other species.

|

| Early morning birds on the Vembanad |

And as I readied for slumber, I reflected on the irony that rain, rivers, backwaters, tears of laughter or grief - all form an integral part of our existence. The human existence in it its many facets, brought forth to ponder upon through the art extravaganza of the Biennale, is fraught forever with error and misguided evaluations leading to pain, inflicted by self or others. Whether it was walking through the Pyramid of Exiled Poets, reflecting on the changes in society brought about by imported ideas, the fragility of nature, haunted memories of an abandoned past or redefining gender, all these expressions arose from a some kind of an ache. The Kochi-Muziris Biennale art was therefore a constant reminder that the ‘experience’ of life, which eventually salvages the lost sense of self in our knowing, almost always come through the mistakes we make in our unknowing. That the nature of human consciousness is one that merges or emerges from that proverbial 'Sea of Pain'.