On my first day in Kochi, I hadn’t gone to the Biennale venues, choosing instead to take a sunset ride on the Vembanad. I wanted to go alone, in a country boat, without a motor, and somehow my hosts could organise this for me at short notice. I spent a delightful hour watching Peter, a fisherman cum sand transporter, manoeuvre his boat through the backwaters with a bamboo pole called karkol. The setting sun played all kinds of ‘light’ games with his silhouette, as his tall, lithe frame, turned the dark, long, wooden boat this way and that, or just letting it float in the rippling waves.

|

| Anjalee looking out at the Pyramid of Exiles |

It was a photographer’s delight and I took almost 300 photos in that hour. Occasional fishermen in smaller boats passed by and Seagulls, Cormorants, Kites, Eagles and Crows flew past or overhead. This, my first day in Kerala was steeped in such wisps and views of the natural world amid the bustle of a successful commercial port that, I couldn’t help but envy the residents of Kochi who were blessed with the facilities of a city and the tranquillity of nature always so close by.

|

| Breakfast in Kochi, overlooking the Vembanad |

The next day, I met up with Maggie Baxter who’d flown down from Australia and Anjalee Wakankar who’d adjourned her Ayurvedic medical treatment for the Biennale, and got down to some serious art viewing. The way the exhibition venues are planned, one walks through different parts of Kochi, passing under the tall canopies of the overarching, shady ‘Rain Trees’, through the perfumes of myriad flower oils, masalas and fish aromas, added to which Dutch and Portuguese architectural accents, Chinese fishing nets and naval dock yards, make the viewing experience a uniquely enjoyable one. Everything mingles in the mind, making it a truly sensual experience, much beyond Biennale art.

|

| Under the canopy of Rain Trees |

As I looked back on the days’ viewing, in my recall, it was the last set of works I saw which came to mind first. At OED Gallery, on Bazar Street in the heart of the spice market of Kochi, were many interesting works that didn't come under the official Biennale banner, but were delightful to view, nonetheless.

|

| Biennale Collateral Event curated by Helen

Rayment ‘Common Ground: the serendipitous happenstance project’ |

Madhubani artists Pradyumna Kumar and Pushpa Kumari collaborated with Ishan Khosla (Bangalore) and Mandy Ridley (Australia) to create fascinating, floor to ceiling, black and white scrolls on coated fabric panels, that transcended boundaries of culture - unique because of the visual and ideological exchange that created the forms, lines and language of visual communication. There was a distinct sense of the 'Western' style of drawing with an 'Alice in Wonderland' touch, but it was also refreshing to see a new vocabulary of marks and narrative emerging from ethnic artists that are wont to regurgitate ideas that don’t always resonate with the world we live in.

|

| Godh - in the lap of nature 2016, |

|

| Godh - in the lap of nature 2016, |

In ‘Godh: in the lap of nature’, 2016, the fluidity of Mithila lines and their naive representation of subject were seamlessly interwoven with skilful, realistic drawing techniques. I was intrigued: who drew them? Was the collaboration one where Ridley and Khosla conceived and gave sketches which the duo from Mithila inked, or were the marks a collective endeavour of the four artists. As part of a Biennale Collateral Event curated by Helen Rayment in ‘Common Ground: the serendipitous happenstance project’, this collaboration was based on collective memories of experiences in nature and from landscapes of childhood. And the different drawing styles of each of the artists were synthesised through the digital reproduction process. I wasn’t sure what stories these scrolls told, but the lines and marks tugged at my imagination and like Alice, I was tempted, but didn’t linger long enough to go down the rabbit hole.

|

| Godh - in the lap of nature 2016, detail |

|

| Godh - in the lap of nature 2016, detail |

In a complete shift from these playful drawings, Ales Steger in creating 'The Pyramid of Exiled Poets' at Aspinwall House, nagged at my conscience, compelling me to enter and experience what it feels like to walk in a world where your voice is unintelligible; where strangers, and not your kinsmen who share language and cultural values, hear your words. What does it feel like to be in exile, to have lost your home and not be heard? And if heard at all, to speak in a world darkened by the knowing of your unknowing?

|

| Ales Steger 'The Pyramid of Exiled Poets' |

Invited to experience that articulated but unutterable anguish of separation and the pain of not belonging, I entered a life-sized Pyramid - emblematic of life after death, which was covered with cow dung. Walking through a pathway, dimly lit as if from below, I tread carefully through a maze of dark passages within the triangular space created by woven mats that partially obscured the light. As lightness got dim and darkness grew so dark as to engulf me, and whence I could barely see, I felt as though I had somehow been suspended in mid-air. My stride was hesitant and taking small, tentative steps, not knowing where or what to put my foot upon and what I could step upon, the only sense of humanity around me was an aural one. Poems spoken aloud in unfamiliar tongues became my guide. As long as I could hear something I was reassured that I hadn't taken a wrong turn (even though there wasn't scope for it). As the blackness enveloped me, I experienced the suffocating darkness, evocative of those who have been summarily dismissed or cast out of public consciousness - whose ideas have been stifled and exiled. It was a disturbing experience but one that left its mark. If anything marred, it was the nervous giggles of a group of youngsters who walked ahead and behind me. But even so, the darkness and sense of insecurity was consummate enough to taunt me through the day, reminding that we are all exiles, where the human experience itself is one of banishment from the kingdom of heaven.

In another gallery, inside Aspinwall, on the first floor. There was an installation with numerous brown ceiling fans accompanied by the occasional, sharp, rasping bark of an unseen dog. Placed just above the stairs on the landing of the first floor, this installation by Lantian Xie who lives and works in Dubai: ‘Ceiling fans, stray dog barking, Burj Ali’, became a passage beyond that of a space connecting floors and rooms. The strange, sharp rasping bark of the dog was to echo through the gallery spaces within and without and even if I wanted to forget, I could not. Like the restive and traumatised spirit of a soul that hasn’t found peace, this dog and the memory of those fans haunted me as I made my way through the other exhibits. Was this ghostly bark the voice of another exile?

|

| Dai Xiang - 'The New along the river During the Qingming Festival', 2014, detail 1 |

Moving into the adjoining gallery, we found that by contrast there wasn’t even one ceiling fan in this room. The afternoon was balmy and humidity was high after heavy rainfall the night before. We were hot, uncomfortable and peeved enough to ask why there was just one pedestal fan in the corner of this long room, to be informed it was so as not to disturb the paper scrolls on display. And somehow, we accepted this explanation without demur because by this time, the sheer scale of the scrolls and intense detailing had engaged us totally. Much discussion ensued between Maggie, Anjalee and myself as to how it had been done and naturally none had the answers. The horizontally positioned 115 x 2500 cms long scroll by Dai Xiang - 'The New along the river During the Qingming Festival', 2014, juxtaposed traditional modes of transport, dress, customs and architecture with the contemporary, and presented an engaging dialogue between layers of culture that interact to form and transform into present-day society.

|

| Dai Xiang - 'The New along the river During the Qingming Festival', 2014, detail 2 |

Inspired by Zang Zeduan (12th century, Song Dynasty) this panoramic, 25-metre-long photographic scene, which had been digitally ‘sewn’, highlighted the socio-cultural conflict from 1970/80's and the opening up of Chinese society, between imported Western ideas and local Chinese traditions. Re-imagining the Qingming Festival, artist Dai Xiang transformed a monumental social-cultural shift through subtle satire that was gripping not just in its Chinese context, but one which provoked much thought regarding India's own cultural confusion and the layers of history which, though assimilated, are still distinguishable as separate from local traditions. And Fort Kochi - it's Portuguese, Dutch, Syrian Christian and British accents in architecture and cuisine juxtaposed with the distinctive indigenous culture of Kerala, created an evident parallel to mull upon.

|

| Dai Xiang - 'The New along the river During the Qingming Festival', 2014, detail 3 |

Pondering upon the amalgam of intertwining cultural influences, I reflect back to the exhibits at the OED galleries in the Spice market area, particularly Maggie Baxter's (Australia) collaboration with Kirit Dave (Kutch). ‘The Poetics of Nothing’ 1,2 and 3, were three scrolls on hand-woven fabric, block-printed and embroidered, with marks composed formally within an ellipse with the same ‘block’ overprinted in varying intensities.

|

| Maggie Baxter and Kirit Dave, 'The Poetics of Nothing |

Large, tactile, textile scrolls with printed, hand-written text in English became the backdrop for hand-sewn threads to be inserted and hung from this base material. This technique created an illusion - as if the warp and weft of construction had unravelled to now hang from the fabric. It appeared as if the boundary of language had transcended, moving out of the egg-like elliptical form, which dominated the background, evoking a resonance with the essential womb of creation and its energies that create any form desired, encompassing all and nothing in the same breath.

|

| Maggie Baxter and Kirit Dave, 'The Poetics of Nothing, detail 1 |

In keeping with Maggie’s preoccupation with scribbles, scrawls and alphabets, the printed works and marks continued her trade-mark free-flowing gestures enhanced by the ubiquitous running stitch and contrasted by Ahir embroidery diamonds done by numerous artisans, all of whom have been named in the catalogue.

|

| Maggie Baxter and Kirit Dave, 'The Poetics of Nothing, detail 2 |

In another exhibition, also at OED, Krupa Makhija's use of computer keyboard keys to create a map of lost language followed in a similar vein – how languages as marks of culture, are lost or recreated.

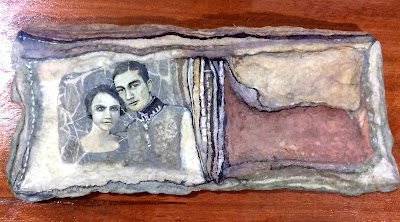

In another work by Siji Krishnan from Kerala, soft colours evoked the time-worn textures carried as memories through photographs and souvenirs collected and often forgotten. In creating the layers of memory, especially childhood memories through small, life-sized wallets using papier-mâché and mixed media the works were so softly hued as to remind one of the many washes they have gone through – the washes of time which form the ritual of creating memories, more imagined than real.

|

| Siji Krishnan |

|

| Siji Krishnan |

Hours of viewing art can take their toll and the mind shuts down, but ‘Art’ also has the capacity to invigorate in precisely such moments. Mikhail Karikis, in ‘Ain't Got No Fear’, 2016, (Aspinwall) a single channel video with surround sound, used the noises of demolition in a recurring beat as young boys ‘rap’ about their lives. It was a compelling video with a mix of cultural references which I could hear but could not discern. But, from the rubble of the site being demolished and the dialogic beat from a complex and sometimes ‘hellish’ language of the past, you heard distinctly defiant voices of the young boys who had made this site their playground that they “Aint Got No Fear”. The juxtaposition of history and cultural voices, echoed the essence of changing values and ideas posed by most of the artists whose work we had seen today. But, it was the recurring beat and an insistently repeated chorus, amid shrill noises of the landscape that, hammered in the weighty question of how much could the human mind really eschew fear.

In another audio-visual presentation, Voldemars Johansons had created a documentation of the stormy North Atlantic Ocean, inviting us to enter a landscape of troubled waters. A large cinematic screen, with massive crashing waves and swirling waters, viewed in a gallery space could not have quite the same intensity of experience as being in the middle of the ocean to hear the roar and feel the turbulence of the waters, and the wind howling and beating around you. But I found myself watching, ‘Thirst’, 2015, (Aspinwall) intently, observing the roaring waves swell and break, to try and fathom what the artist was wanting to show me. Everything else that I had seen till then was momentarily relegated to the back of my mind. And despite the troubled waters before me, I felt a sense of quiet within my being to experience through this 'thirst’ for observation, the vital key towards understanding the ever-dynamic phenomenon of life, of going from without, within. Where briefly we are no longer in exile.

Through the day, I found myself surrounded by varied Art expressions and media, new vistas, water bodies, ships and ferries, spice markets and delicious food that beckoned, and realised how difficult it was to engage with it all.

|

| Maggie at Brunton's Boatyard, Fort Kochi |

We had started our viewing late in the day after an exotically flavoured lunch of Syrian Christian flavours steamed in banana leaf. Our first day therefore, was limited in its art-intake, and with periodic breaks for cardamom flavoured nimbu paani and impromptu shopping for spices, though slowing us down, also gave us scope to sit back and let the mind wander in other directions, to let art we did see, sink in effortlessly.

|

| Spice Market |

Yet, the Art that we did see, left their scars, created parallel dialogues in my mind and invoked the spirit of intercultural influences, through trade, colonization or displacement - absorbed and amalgamated into the ever-dynamic traditions that we inherit and pass on. But above all, this first day of my viewing of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2017, created a thirst in me. That perennial thirst to know and understand the human experience, articulated through the visions and voices of artists from across the world: was it truly a universal one, and how much did the external world and its unique contours matter, in the ultimate analysis of things.

3 comments:

God!! going through your post was just sinful. I am headed to Kochi in the last week of the Biennale and hope to catch this action.

Please let me know of any tips/ resources - places to see / eat, etc that should not be missed.

Cheers

Thanks for reading. Sinful....why sinful, am most curious.

There is so much to see and do that I just let things fall into place. I have another two days of viewing to share. Will post shortly. Perhaps you can identify what you'd like from them.

Very insightful..i am going for 2 weeks some time later in the year!

Post a Comment